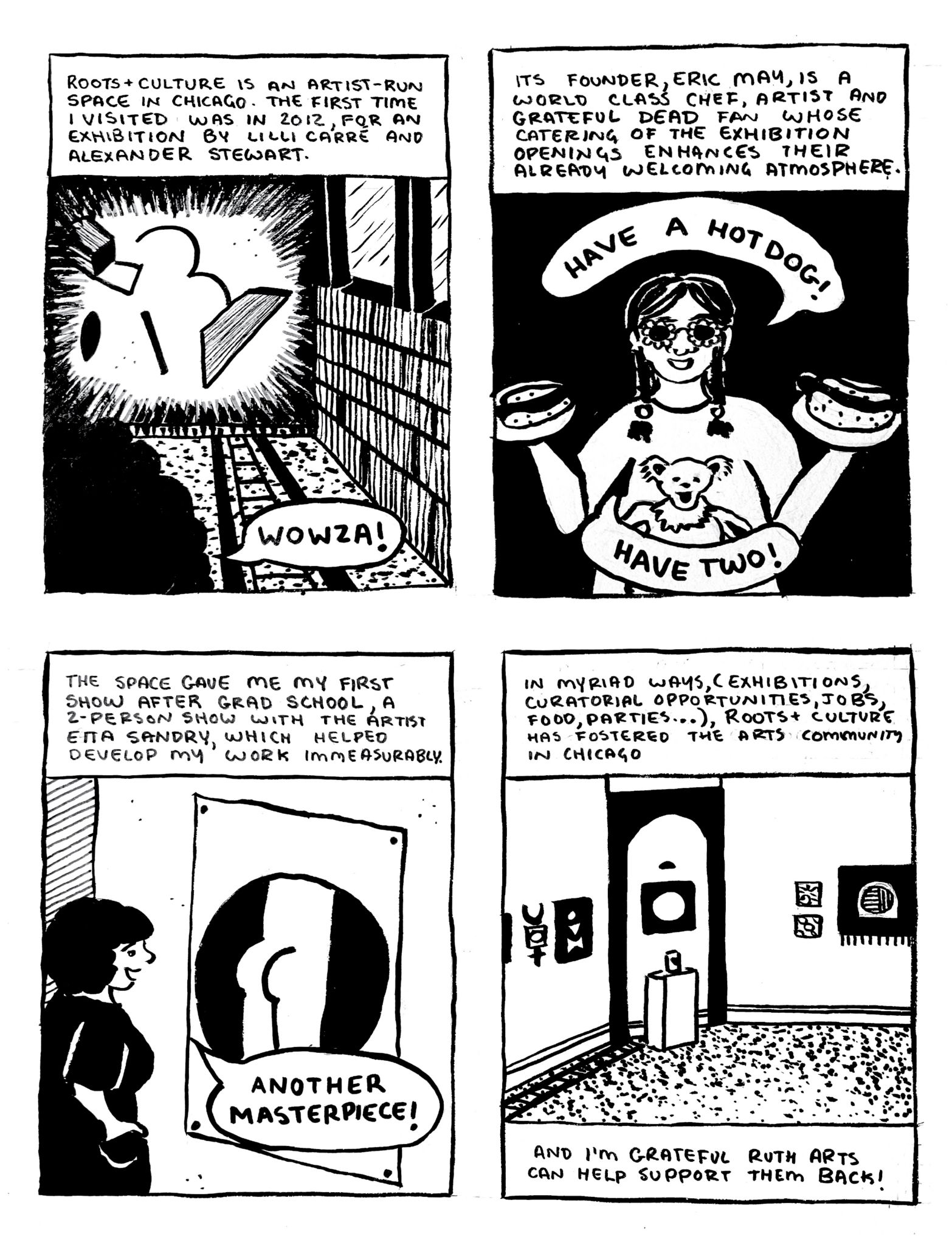

We initiate programs that reflect the fullness & interconnectedness of artists’ lives and practices. Our programming honors the inimitable Ruth DeYoung Kohler II in the way we know best: with a willingness to enter into irresolution, to be unsettled and surprised, to learn and unlearn, to always aspire for more. And to do this together.

Learn More